The Age of Pan - Part 2: The Knowledgeable Ape

Why are people upset about synthetic images winning art prizes?

You might have heard: Someone took the first prize in an art contest with a piece generated by the AI-system Midjourney. The guy won 300 Dollars and a lot of people are very upset about this.

Now let's get a few quibbles out of the way: 1) I don't think that art is something that happens at the Colorado State Fair, ever, and 2) to understand why artists are so upset, you also have to understand the immense economic pressure in the creative market. The democratization of image crafting through digital tools and online marketplaces for creative assets have devalued labor in the creative field for at least 20 years. And suddenly a machine comes along and creates funny white robot rabbits in the style of Jean Giraud with zero effort and no skills involved and wins art prizes too.

I do digital creative works since I was 10, did graffiti for a while as a teenager and worked in the creative industry for more than 25 years as a typographer and illustrator and webdesigner. One of the more sacred things in creative spaces is style. Good artists steal, but they also incorporate stolen styles into their own to synthesize something new, they don't just grab it and draw a funny picture of a cat.

So yeah, I get it.

But there is more at work than economic pressure in the market and jealousy at automization.

To find out why the debate is so heated and why artists are so upset, we have to find out, what art really is and what it means and for this, we have to find out what humans really are. (Yes, the rabbit hole is really, really deep.)

So, let's go back in time, right to the moment when we crossed the line from "social animal" to "homo sapiens", the "knowledgeable man", the beast that is able to know.

What does that mean, exactly?

Yummy Yellowfruit and the Invention of Art

Knowledge is a form of data compression. We compress data in information about our environment by observing patterns and extracting the essence from these patterns, storing this compressed data in our memories and this is what we call “knowledge”.

We eat bananas once, twice, three times and make a few observations: a) we don't die from eating bananas b) they taste good c) they are nutricious and fill our bellies very well d) they grow upside down in large chunks of bananas and can easily be gathered e) they can be easily peeled and eaten and f) we can use the banana peel for all kinds of other stuff. Based on these observations, we make bananas a regular part of our diet. The compressed knowledge we extracted from these observation is something like: "Bananas are a good, usable, flexible meal, are peeled in a special way and they look funny", and we compressed this information into this knowledge from repeating patterns gathered across multiple sessions of "eating bananas". This is how we generate knowledge.

But animals do that too, to some extend. Crows can generate knowledge and show intelligence, even social intelligence, which brings us to the next step: First we became social animals observing our environment and then we learned to share this compressed information aka knowledge aka patterns we extracted from repeated actions.

For this, we developed what Michael Tomasello calls shared intentionality. We now have an essence of bananas in our head, a pattern of what we can do with them and how we can do this in the most effective way. We don't need to think about every detail of banana identification and banana gathering and banana eating every single time we want some. Based on this we can now share our knowledge of bananas with our fellow apes, for which we developed a technique to communicate our intentions: language.

Step by step, first with gestures then with grunts and sounds then with words, we learned to make our fellow proto-humans understand what we want. Suddenly, we were able to point at the banana tree and say "you gather yummy yellowfruit while i make fire". This made us into some very, very effective social animals back then and this way of turning bananas into a symbol in our head with which we could play, put all kinds of funny things in our brain, like the ability to imagine that our fellow apes had a mind of their own.

But animals hunt in packs and they communicate, so they have at least some form of shared intentionality too, right? They might not have a theory of mind, but Tomasellos shared intentionality and the consequential hypersociality can't be the only thing that makes us human, I mean ants and bees are hypersocial and they share knowledge where to find food, so what’s up with that?

This is where the knowledgeable ape meets the permanent fixation of knowledge onto a medium through externalized symbols.

At one point between 64.000 and 40.000 years ago, the first protohuman put his hand on a wall in a cave in spain and fixed the shape of his spread out fingers with pigments, producing the very first work of art. For this, she had to get a bunch of ideas in her head about her hand, the shape of the hand, that it would be funny to see that shape on the wall, maybe she even thought that sharing that funny shape of her hand with her fellow protohumans would delight them and tell them something about her hand, the shape of her hand and the very fact that her hand, that usually is part of her body, now is a funny picture on a wall. Maybe it would make them laugh, maybe she would get more bananas from her tribe.

Given that no animal did anything similar until that moment, this was a remarkable evolutionary step. That was the moment when an ape discovered the possibility of knowledge transfer across periods of time. This first human who put the shape of his hand on a wall in a cave opened a communication channel with their own past and made it possible to speak to future versions of themselves, to give them an idea about what was going on in her head, at this particular point in time and space.

From this moment on, knowledge was no longer bound to any individual and the ideas in her head, nor was it bound to a moment in time when the individual spoke in vibrating air molecules (aka language) to his fellow protohumans. From now on, we were able to fix knowledge onto a medium and preserve it, look at it weeks, months, years later and get an idea of what the protohuman was saying with it. This was the moment when we learned to not only compress information into knowledge, but to preserve and build on it.

We learned to turn ideas into abstract shapes and fix them on a wall, so that future generations were suddenly able to worship the same gods, grasp the same concepts and communicate with and about knowledge itself. Historian Jan Assmann has written extensively about this step from social to cultural knowledge transfer and he describes this invention as the formation of a cultural encoded collective memory.

This invention of a playful technique for transforming knowledge into symbols on a fixed medium and by this — nearly as an accidental tangential side product — the formation of a culturally encoded memory, which was first visible in art and paintings, is what truly makes us homo sapiens, the "knowledgeable man": The beast that is able to accumulate knowledge over time, making it speak to people in the future, so they can build on those thoughts from the past, frozen in artifacts.

Image Synthesizers like Midjourney, Dall-E and Stable Diffusion not only automatize the process of creation of symbols — a typewriter does the same, in a sense —, they also add a stochastic element to their creation.

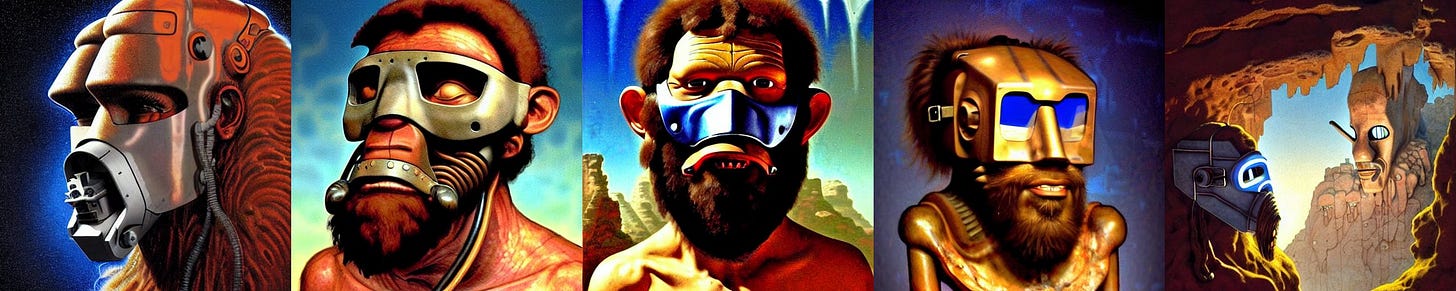

When that first human put his hand on a wall in a cave in spain, he had a more or less precise idea about his hand and the shape and the resulting symbol. Image Synthesizers dissovle that precision and give us something else instead: A vast latent space of visual imagery that can be endlessly remixed and combined and which we navigate via text inputs to discover stuff that nobody has seen before — an ocean of fluid artifacts from parallel universes, in the style of all artists.

This is fundamentally different from turning knowledge into symbols and drawing them and artists can instinctively sense what’s at stake here.

In Arthur C. Clarkes book-version of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the black monolith is translucent and releases rapid animated whirlwinds of colors, working like a psychedelic screen displaying all kinds of weird shapes and forms to the apes, which in turn kickstarts human evolution through some sort of perceptive overload. The invention of art was, in a way, exactly like this and who knows what image synthesis will add to that.

This is the reason why the debate about AI art is so heated: it points right at the heart of the question of what it means to be human, the ape that can accumulate knowledge by drawing on a wall.

Hi, thanks for your article.

I don't quite understand this part: "Image Synthesizers like Midjourney, Dall-E and Stable Diffusion not only automatize the process of creation of symbols "...

Does AI in its current state understands symbols?

https://www.bcs.org/articles-opinion-and-research/does-ai-need-symbols/

sehr geil. vor allem das Ende<3 Erinnert mich an the wandering god by Morris Berman. wo er über die Fähigkeit aus dem Einklang mit der Natur, das Wunder zu erkennen und wiederzugeben - die wir seit der industriellen Revolution quasi verloren/am verlieren sind. und hiermit das dann ins Digitale übergeht und vielleicht so wiedergeboren wird.